This post is intended neither as an accusation nor as a confession…

Well okay, maybe a bit of a confession…

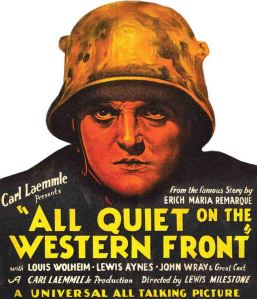

Director: Lewis Milestone

Producer: Carl Laemmle Jr

Studio: Universal

Written by: George Abbott (screenplay), Maxwell Anderson (adaptation), Del Andrews (Adaption and dialogue), from the novel by Erich Maria Remarque

Starring: Lew Ayres, Louis Wolheim

Happy New Year! Let’s ring in 2014 with a seasonal visit to one of history’s darkest chapters!!!

I must apologise for the delay in publishing this post. I’ll be honest, I struggled with this one. I started with all good intentions to post it on Remembrance Day…then Remembrance Day came and I couldn’t quite work myself up into the mood to watch the film (and it is a film for which you have to be in the mood). I finally watched it two days later, and figured that at long as I published the post in November, it would still sort of be Armistice-adjacent…But then I realised that All Quiet on the Western Front was the first Oscar Best Picture to be adapted from a novel, which I decided I really needed to read in order to be able to comment on the film…which set me back a further week, and then work went crazy and Christmas went crazy and suddenly it was January.

So. At long last here is my post on All Quiet on the Western Front, which won the Oscar for Best Picture for 1929/1930. In time for the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War.

My reluctance to watch the film and write this post

I approached Wings with a slightly patronising curiosity and The Broadway Melody with unbridled enthusiasm; the former rewarded me with a wonderful discovery and the latter a stinker (albeit with redeeming features). But without yet having watched All Quiet, I already know that in evolutionary terms it will be generations ahead of its Oscar Best Picture predecessors.

Silent film aficionados may appreciate Wings as a masterpiece; The Broadway Melody may be of academic interest to musical comedy aficionados; but All Quiet on the Western Front is so famous that its very title, from the original English translation of Remarque’s novel, Im Westen Nichts Neue (literally, Nothing New on the Western Front) has long since embedded itself in our culture. You might not have heard of some of the early Oscar Best Picture winners, but everyone has heard of All Quiet, whether you’ve read the book, seen the Oscar winning Hollywood film or seen one of the various other film adaptations. Most people I speak to remember watching or reading it in school, which perhaps goes some way to explaining my reluctance to watch the film.

If I’m dragging my heels over watching All Quiet, it’s not because of any low expectations as to quality. I feel confident it will be very, very good – so good I feel a sort of reverence towards it which is somehow intertwined with the reverence I feel in remembering those who were killed in the First World War itself. There is none of the sense of mystery or anticipation I experienced ahead of the earlier films – rather, the mere thought of watching the DVD I ordered from Amazon (the limited edition Universal 100th Anniversary Collectors’ Series Blue-Ray release, no less) of All Quiet fills me with nobleness and virtue. I take Remembrance Day seriously and wear my poppy with pride, consciously honouring those who fell in the two world wars (and it’s a big diamante poppy brooch, which for David Mitchell’s information is far more practical than, and involved a far bigger donation than most people give for, a paper poppy. And if it happens to chime with my dress sense more than a paper poppy, so what? The pinning mechanism actually works, it doesn’t look disrespectfully crumpled and rubbish within five minutes, and it doesn’t fall off leaving just the useless, naked dressmaker’s pin on your lapel while you wander round oblivious). I never fail to be moved by the solemnity of the two minute silence, and – being possessed of a rather fervid imagination – find it easy to become melancholy in absolutely no time at all, musing over the sacrifices those men and women made. Yes, All Quiet is going to be good, but it’s also going to be gruelling, and watching it does feel like more of a duty than a pleasure.

The truth is, I am inwardly whining about watching another war film, already. We only just had Wings! At this stage, two thirds of all Oscar Best Picture winners are about the First World War. The Broadway Melody seems like an all-too brief and glittery respite which for all its flaws, I am already missing.

Then I watch All Quiet On the Western Front, and it is every bit as brilliant as I am expecting. However, when I read the novel, I am completely blown away. So to speak.

Sorry.

The film may be excellent, but it is, among other things, subject to the technological limitations of the time; the book on the other hand is as fresh and raw as if it were written 10 years ago instead of 90. Change a few of the details and you feel it could credibly have been written by a veteran of Iraq or Afghanistan. This left me in something of a quandary over how to write about the film, which the book had completely overshadowed.

But this blog isn’t about novels, it’s about films. So having left enough time for the impact of the novel to clear from my impressions of the movie version, and for my reverence for those who fell in the First World War to untangle itself from my appreciation of the film, I think I’m finally ready to write this post.

The plot

The war has started. An elderly German schoolmaster persuades sixteen-year-old Paul Bäumer (Ayres) and his fellow classmates to enlist in the name of the fatherland. The boys join the army and are sent to the western Front.

Survival of the fittest

A big criticism of The Broadway Melody, both then and now, was that after years of innovation in silent movies, the film utterly failed to exploit the medium of film: it often seemed like a (somewhat amateurish) recording of a (somewhat amateurish) stage play. All Quiet on the Western Front marks a return to the dynamic film-making and story-telling evident in Wings, and reassures us that The Broadway Melody was indeed a blip in this respect – presumably while directors got to grips with Talkie technology. Apart from anything else, All Quiet is a reminder of just how advanced motion picture directing already was by the advent of the Talkies. A war film, with its prolonged battle scenes and action sequences, is in many ways the ideal material for that difficult transition from silence to sound, naturally relying on action over dialogue to tell the story. It sure makes the whole concept of The Broadway Melody seem nothing short of foolhardy: for your first foray into Talkies, pick a genre that relies on sound over everything else! I can’t help wondering whether the movie musical were viewed at the time like some kind of hideous Darwinian mistake. No wonder it would be more than two decades before another musical won the Oscar Best Picture (An American in Paris, in 1951).

Film versus book

The briefest of comparisons between the book and the film reminds you that there are certain aspects of a novel that cannot easily be reproduced on screen. But on the other hand, film has certain alternative techniques at its disposal. On the whole, the choices made in adapting the novel of All Quiet to the film maximise the opportunities that film affords and dispense with aspects of the novel that do not easily lend themselves to a visual medium.

For example, the novel is told in the first person by Paul, and jumps around in a series of flashbacks and reminiscences. Chronologically, the novel begins about halfway through the story. The opening scene is the men of B Company tucking into a bountiful feast…only two pages later is it revealed, through the soldiers’ paradoxical horror and delight, and the cook’s blackly comic bewilderment, that the sheer quantity of food is a result of the meal having been prepared for the hundred and fifty men who had formed B Company that morning. By the time B Company returns for dinner, only 80 are left.

It is a shocking beginning that has such impact that I was initially surprised the film opens with a woman mopping the floor of a room while an elderly man polishes the doorknob:

“Man: Thirty thousand!

Maid: From the Russians?

Man: No, from the French. From the Russians, we capture more than that every day.”

(I must admit, that while my Blu-Ray version has been digitally restored in HD, the sound quality is poor and I had to google these opening lines to understand what they were saying).

I wondered why the writers had squandered the opportunity for such a dramatic beginning in favour of this mundane scene. However, I soon changed my mind as it became clear that the writers had made a wise decision to tell the story in chronological order from start to finish, allowing us to invest in the characters as their story develops, and show the impact of events without the tricky business of recreating the interior monologue which takes up much of the novel. The cleaner’s enthusiasm and pride in the German war effort, from which he himself is safely removed, neatly sets up a key theme of the novel: that of anger towards an ignorant older generation which willingly send their young men to a war, the horrors of which they know nothing.

From lightness to the dark: the doorways to Hell

After that first snatch of dialogue, the door to the room opens onto a bright and pretty street framed in the doorway. The camera exits through it to a vision of the old cleaner’s pride: in the sunshine, troops are marching with smart regularity while women and children wave them smilingly on; well-dressed ladies are shopping and people are going about their business while a military band strikes up.

Every shot, even that of a market stall, is architecturally framed: geometric doors, arches and windows dominate the screen. The camera eventually pulls us from the happy bustling and pageantry in the street into an airy classroom, where two large windows flank a blackboard covered in Greek writing. The overriding visual impression in the first few minutes is of light, space, cleanliness, symmetry – in short, of civilisation.

Latine dictum, sit altum videtur

In front of the blackboard stands the schoolmaster, forming a tableau with with the windows either side of him and the street scene beyond. He is fervently exhorting and manipulating his pupils to enlist, as if carrying the patriotism and fanfare of the street through the windows and into the room where the schoolboys sit quietly behind orderly rows of desks. Rousingly he notes that ‘if losses there must be, then let us remember the Latin phrase, which must have come to the lips of many a Roman when he stood embattled in a foreign land: Dulce et decorum est, pro patria mori!’ The concept of war is filtered through the uniforms and brass instruments of the troops marching outside, through those large and civilised windows, through the kind of classical education which represented the pinnacle of the civilised world.

Duly roused, the boys decide on the spot to enlist en masse, and throw their school papers in the air in ticker-tape parade style celebration. Someone crosses out the Greek on the blackboard and scrawls ‘Nach Paris’ (‘to Paris’), before all the boys rowdily march off together, singing their own patriotic song in imitation of the soldiers outside. We see them pass happily by the two big windows, and then the camera lingers on the empty classroom, floor and desks strewn with papers.

Afterwards, the abandoned, messy room is the first sign of a gradual descent from the rarefied heights of civilisation to the primitive depths of war.

The beginnings of disorder

The first step down is at the training academy, where there are signs that things are out of kilter: the boys’ uniforms don’t fit and they aren’t allowed any leave to meet girls to impress. These ambitions are thwarted by Himmelstoss, a character who in the initial street scene is depicted as a friendly postman, but has now ‘changed his uniform for another’ and become a power-crazed and sadistic drill-sergeant, constantly forcing the boys to lie down in the mud. The muddy training grounds are a foretaste of what awaits them at the front; although by and large, visually the training scenes are framed by more geometrical windows, arches and cleanly-swept courtyards. Even the mud is neatly ploughed into regular troughs.

The first major change comes at the front, when the boys arrive by train at a bombed out village. In stark contrast to the town they have left, buildings are in ruins, the road is a mudbath, and chaos reins with carriages, horses and troops hurrying around confusedly. The camera alternates between viewing the confusion at street level, and dispassionately viewing the scene through another large window, from the peace and safety of an unidentified interior. It is from this viewpoint that we see a bomb go off and then up close, the boys all dive for cover. There are no more nice windows after that: it’s as if this window, the location of which is never explained, exists solely to represent the final divide between the civilised, ordered, sheltered world, and the chaotic unprotected world of war.

A room without a view

The boys’ first digs are a ramshackle room in a dilapidated old barn with no sleeping quarters or food. The windows are boarded up and the doorway only ever seems to reveal rain and darkness.

A soldier through the door…looking slightly different to the marching troops viewed through the doorway in the opening

However, the real low point is the dugout at the trenches, a nightmarish parody of the light and airy rooms so prominent at the beginning of the film. Instead of sharp, clean lines, crudely assembled beams soften the corners and lower the already low ceiling. With every shell that goes off, the dugout shakes and dust showers down inside the cramped space. The dark walls are rough and dirty, and the men are dirty too. The more shells that go off, the more broken down and filled with rubble the bunker becomes. Rats are jokingly referred to and vigorously attacked with spades, in a scene that prefigures some of the hand-to-hand combat to come (although one that sanitises the source novel – I found the descriptions of rat infestations almost more harrowing than the battle scenes themselves). It is not hard to believe either the terror of the soldiers, or their comradeship in surviving the blasts together in this confined space.

Having illustrated this regression from refinement to the primitive (though unlike the novel, the film desists from depicting the reality of the lavatorial arrangements), the film visually prepares us for the ultimate nadir: trench warfare and the battlefield.

Those battle scenes

In my post on Wings, I mused over the apparently trivialised depiction of trench warfare as compared with the brilliantly filmed dogfights. All Quiet however, is the blueprint for ground battle scenes on which countless war films have been based.

Just as Wings ingeniously filmed from the pilot’s view as well we filming the pilot up close, the masterstroke of All Quiet is to film from the angle of the trenches themselves. The camera peers over the top at no man’s land, waiting for battle to commence, then pans across the row of soldiers with guns nervously waiting to fire.

The brilliance with which the action of the first battle is built up is matched only by the cleverness of the camerawork. The first shells go off, and the battle scene builds up: explosions in the mud, craters forming, gunfire. Then men are seen running from the horizon towards the trench, and the enemy has a human face. The camera pans out to reveal the hundreds of men on the ground, running, and then back in to show them falling, or running through water-filled craters or jumping over corpses. Meanwhile the Germans are firing, and in one of the most memorable sequences in the film, the camera is seemingly attached to a machine gun. As it sweeps from left to right, we see the barrel’s eye view of man after man being hit and falling down in clouds of dust and tangles of barbed wire. The scene is chilling: in mimicking the movement of the machine gun, the camera depicts the machine’s ruthless efficiency and relentless, robotic drive. I found myself riveted, mouth gaping stupidly, lips curling up in horror.

Chaos reigns as the enemy’s men get ever closer to the trench and every soldier must use anything at his disposal to survive. In one moment, a soldier is holding onto the barbed wire fence in front of the trench; the next, only his hands are left.

Soon the enemy is rushing towards the trench with bayonets outstretched and jumping in, where in that confined space men stab each other, shoot each other and hit each other with spades – much as they hit the rats – to end the battle.

A terrible, terrible scene – but one area in which the film has greater impact than the novel. Powerful as the book is, I am not a military expert, and when I read lines like “Three guns fire out just beside us. The gunflash shoots away diagonally into the mist, the artillery roars and rumbles” (page 37, Vintage edition 1996), I find it quite difficult to imagine what that actually looks and sounds like (“curtain fire” also features – what on earth is that?). I may not be able to tell the difference between ‘artillery’ and ‘a coal-box shell’, but the experience is nevertheless brought to me on film in a way it cannot be in the book.

These boots were made for telling a poignant tale, economically on film

A beautiful example of how the film really exploits its medium is in the story of Kemmerich’s boots. In an early scene at the training academy, when the boys are all still brimming with juvenile enthusiasm, Kemmerich brags about his fine boots, which his uncle gave him. When Kemmerich is in the field hospital, having just had a leg amputated, the existence of his fine boots which he can no longer wear is central to his emotional and physical decline. When he dies, Müller ‘inherits’ the boots and the next shot is a close-up of the boots marching, before panning out to a pleased-looking Müller who is quickly killed. A random soldier, not one of our boys, is then shown happily wearing the prized boots, which we infer he has pulled off Müller’s corpse. Another close-up: the bottom of a ladder in a trench. We see the boots climb up the ladder out of shot. The camera doesn’t move. Nothing happens for a moment – we are still looking at the bottom of the ladder. Then we see the boots fall lifelessly down to the ground.

Action versus horror

If Wings owes much to the action genre, depicting something of a boys own adventure version of war, some elements of All Quiet have more in common with horror. The visual descent into darkness, and vignettes like the hands on the wire (taken directly from the novel) are two examples of an almost gothic sensibility apparent in the film.

In one scene, the soldiers are under attack in a country churchyard. As Paul dives for cover, he gratefully grabs a large timber box for cover, before recoiling in horror and shoving the timber away as he realises it is a coffin and he has unwittingly sheltered in a grave.

In fact, this is another sanitised version of an account in the novel, in which it is a military cemetery under attack and Paul and his comrades are grateful for the shelter the corpses and coffins provide (“They have been killed for a second time. But every corpse that was shattered saved the life of one of us” – page 49, Ibid). Presumably, audiences were deemed not quite ready for this.

The soldiers

Paul Bäumer – the central character

Lew Ayres is well cast as Bäumer: good looking enough to be a leading man, but not so striking as not plausibly to be an everyman. His delicate features lend themselves to the role of a would-be poet, and he acquits himself well, if not effortlessly, in what is a challenging role. He is perhaps a little smooth for my taste though, and around half way through I realised that something had been bugging me about him: in looks, demeanour and intonation, he reminded me so strongly of Mad Men‘s Pete Campbell, that I even wondered whether Vincent Kartheiser had based the character on Ayres’ interpretation of Bäumer:

“You still think it’s beautiful to dye for one’s country. The first box of Just For Men taught us better”

Katczinsky – the avuncular older friend

Louis Wolheim is wonderful as father-figure Kat: charismatic and likeable, his good-humoured yet authoritative presence on screen is as reassuring as a declaration of peace.

The rest of the cast are all excellent, but it’s difficult perhaps to understand how a contemporary audience would have appreciated them. For example, the vaguely comic character Tjaden is played by Slim Summerville, a well-known comedy actor at the time. My guess is this would have created more light relief than Tjaden really creates in the film or novel – kind of like Sacha Baron Cohen in Les Miserables. In another famous scene, again taken from the novel, Paul must spend a day and a night sheltering in a crater with the body of a man he has just killed. Paul at first watches the man dies a slow, gurgling death, before becoming hysterical and talking to the corpse. Raymond Griffith is uncredited as the dead French soldier Gérard Duval, but was apparently also a well-known comic actor at the time. How would this have affected an audience’s experience of that scene? Brought home the death of a real person more forcefully – or undermined it?

An evolutionary crossroads

All Quiet on the Western Front is particularly interesting from an Oscar Best Picture evolutionary perspective. It looks clearly to the future – dialogue and sound effects have been mastered, cinematography continues to innovate, challenging subject matter is tackled. According to the blurb accompanying my Blu-Ray disc, Lewis Milestone started his career as an assistant film cutter, and it shows. The confidence with which he directs the battle scenes easily rivals Wellman’s confidence in the air.

However, it also cleaves firmly to the past, to the action tradition exemplified by Wings. Whilst the dialogue may seem practically fly-on-the-wall naturalistic when compared with the awkward clunkiness of The Broadway Melody, it retains a staged quality that still calls to mind the theatre again. A limitation of production at the time is the lack of a soundtrack; this has served the film well – the silence before the battle breaks out creates more anticipation than any mood music could. However, what the film is crying out for, but was presumably unable to produce, is a voice-over narrative.

Instead, some of Paul’s existentialist musings become soliloquies in the film. A speech or two is fine, but there are one or two too many, either to seem realistic (would these soldiers really speak to each other of such things?) or naturalistic. Again, it’s a style that would make more sense on stage.

Why no gas?

If you’ve read any poetry of the era, you will be familiar with the vividly depicted gas attacks. I was surprised therefore that not a single gas attack features in the film, and was curious to see whether the same would be true of the book. It isn’t: there is one standout scene in particular involving a gas attack on the battlefield. Curiouser and curiouser – it seems like it would be relatively easy to film someone ‘flound’ring like a man in fire or lime’. However, reading this chapter it also dawned on me why gas had been edited out of the screenplay. If everyone is wearing a mask and uniform, how could the audience tell one character from another? One way would be to have a voice-over (not possible). Another now-familiar trope would be to have a camera ‘inside’ a mask, looking out from one soldier’s viewpoint. Perhaps Milestone didn’t think of this; perhaps he did but couldn’t make it work. Without being able to hear breathing inside the mask, what would it really add anyway?

Whatever the reason, this rather glaring omission in the adaptation serves as a reminder that All Quiet on the Western Front may represent progress and set a new standard for the Oscar Best Picture – but there is more, so much more, for film-makers to learn.

What an exciting juncture in our Oscar Best Picture journey. Looking forward to our next film, Cimarron.

It’s going to be extremely tough for anyone of our generation to put ourselves in the minds of the audience of this film. The vast majority of the original British audience will have been directly effected by the Great War, either through combat experience or knowing someone who had served in HM Forces during the war. This was real to them in a way that it isn’t for most of us.

Due to my strange MA (War Studies, KCL) I’ve met quite a few professional military and strategic types, some of whom remain close personal friends. I’ve seen what PTSD does to people. BUT they were volunteer professionals, who chose to be part of self consciously elite forces.

The difference the the First World War is that, after the retreat from Mons and first Ypres, where the old British Army was effectively wiped out (after gutting the Germans and fighting them to a standstill) Britain had to come to terms with mass industrialised warfare and a civilian volunteer and later conscript military forces, quite unlike anything in its social, political and military history.

The other thing that is really interesting about AQOTWF is that it’s about Ze Chermans. They had been the enemy, but due to the purity and universality of ghe source material, the human experience of the Great War was emphasized. One of the few modern war fils that sometimes gets this is “Three Kings” http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120188/. Even then, it’s more of a cynical MASH / Catch 22 satire than an attempt to see the wold through the eyes if the enemy.

I’ll stop now because I’m rambling. Thanks for a thought provoking and well written blog. What’s next?

PS, gas wasn’t as prevalent as Wilfred Owen’s incredible poetry may have suggested, due largely to battlefield technology making it more of an area denial weapon than a precision munition. As often as not, it cause as much trouble to the users as to the intended victims. Wasn’t until 1918 that it could be used as an all arms integrated application.

Thanks for the comments Padsky! I actually think Catch 22 has more in common with All Quiet than that – the same urgent need to convey the horrifying reality of the experience. Only Catch 22 uses absurdity versus the confessional of All Quiet (despite the preamble)…that’s my somewhat glib response anyway! Not seen the film adaptation of Catch 22. Thanks for the info and tips on gas! Look out for my post on Cimarron, about the Oklahoma land rush x

Pingback: 4. Cimarron – Help, Superman, the wheels are coming off | As Time Goes By...